Chronic renal disease (CRD) is one of the most common diseases seen in older cats, reportedly affecting one in three cats over the age of 12 years[1][2].

Chronic renal disease can appear as acute renal failure or as an insidious chronic renal insufficiency, which is more common. Many cases are associated with age-related chronic interstitial nephritis[3]. Anaesthesia-risks associated with this condition are considerable, and routine anaesthetic procedures such as dental descaling and extractions are associated with a higher mortality rate in this species[4].

Causes

The most common cause of chronic renal disease in cats is the slow and insidious age-related syndrome of interstitial nephritis (also known as chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis).

Interstitial nephritis in cats occurs as a result of oxidative stress and reduced antioxidant capacity[5]. As the disease progresses, a vicious cycle of self-perpetuating renal injury referred to asinherent progression. This state is characterised by glomerulosclerosis, glomerular hypertrophy, interstitial cell infiltration, and interstitial fibrosis with multifocal thickening of the Bowman’s capsule[6][7]. In some cases, amylin protein fibrils are deposited in the glomerular basement membrane and mesangium leading to renal amyloidosis[8]. Secondary renal dysfunction occurs, leading to altered water regulation, altered production of renal hormones such as renin (increased in CRD; with increased stimulation of RAAS enzymes), calcitriol and erythropoietin (both decreased in CRD).

Long-term oxidative stress in cats is often seen in diseases such as chronic viraemia (e.g. FeLV, FIV, FHV, FCV) and parasitaemia (e.g. Bartonella spp)[9]as well as long-term exposure to dietary toxins (e.g. melamine) and commercial dry-food diets high in protein and acid content, but marginally replete in potassium[10]. Other causes of chronic renal disease include polycystic kidney disease, amyloidosis), nephrotic syndrome and lymphoma.

Clinical signs

Many of the early clinical signs associated with chronic renal disease can be missed by cat owners and are referable to dehydration and azotemia. As renal water regulation and waste excretion diminishes, dehydration exacerbates the azotemia, resulting in toxins (particularly urea, gastrin, creatinine) that directly affect the brain (uremic encephalopathy) and gastrointestinal tract (uremic gastropathy).

Common signs in early chronic renal disease include weight loss, intermittent anorexia, intermittent vomiting, occasional polydipsia and halitosis. There may be behavioural changes referable to uremic encephalopathy, a syndrome unique to cats where azotemia

results in increased night-time vocalising, restlessness, and apparent dementia (which is often reversible with appropriate fluid therapy). Vomiting daily or every second day appears to be a consistent sign in early renal disease, and in advanced cases blood-tinged or coffee-colored vomitus (haematemesis) due to secondary uremic gastritis[11]. In advanced cases, severe dehydration, haematemesis, anorexia and weight loss are significant. Hypertension is frequent due to alterations in RAAS regulation of blood pressure and reduced clearance of vasopressin.

Intermittent diarrhoea and constipation are sometimes seen.

Diagnosis

Provisional diagnosis is based on clinical signs, blood tests and urinalysis. Blood tests in early renal disease are often inconclusive since more than 70% of kidney function has to be lost before any significant changes in urea, creatinine or phosphate levels is seen. A positive correlation exists between renal vasculature resistance and azotemia but not systolic blood pressure[12].

Testing for the presence of proteinuria, microalbuminuria and comparison of urine protein:creatinine ratios (UP:C) are reliable clinical tool to assess renal function. UP:C ratios of >0.4 reflects a four-fold increase of renal failure in cats[13]. Other urine parameters such as Urine cauxin (a feline-specific peptidase pheromone) appears unsuitable as a biomarker of CRD in cats[14].

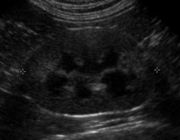

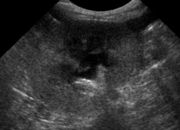

Ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography offers a noninvasive means of subjectively and quantitatively evaluating renal perfusion in cats with renal disease[15].

Definitive diagnosis is based on histopathological examination of renal biopsies.

Diseases which need to be considered in any differential diagnosis of chronic renal disease include ureteral calculi, Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD), Feline upper urinary tract disease (FUUTD), renal lymphoma, renal carcinoma, acute pyelonephritis (immune-mediated, bacterial, viral, fungal), ureteral neoplasia and leptospirosis.

| Stage | 1 – Non-azotaemic | 2 – Mild renal azotemia | 3 – Moderate renal azotemia | 4 – Severe renal azotemia |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | <140 | 140 – 250 | 251-440 | 440 |

| Urine protein:creatinine ratio | <0.2 | 0.2-0.4 | >0.4 | >0.4 |

| Blood pressure | <140 mmHg | 140 – 160 mmHg | >160 mmHg | > 160 mmHg |

| Clinical signs | None | +/- anorexia, weight loss, PU/PD | anorexia, weight loss, PU/PD, hypertension | uraemia, clinically ill |

| Progression | Stable for long periods | Stable for long periods | May progress | Fragile |

| Therapeutic goals | Identify any disease, e.g. pyelonephritis, nephrolithiasis | Identify any disease, e.g. pyelonephritis, nephrolithiasis | phosphorus restriction, omega-3 fatty acids supplements | protein restriction, anti-emetics, erythropoietin, appetite stimulants, SQ fluid supplements, peritoneal dialysis |

Recently, the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS staging system) has developed a standard for gauging the continuum of progressive renal disease. Staging is based on the level of blood creatinine as a function of renal competence[16].

Treatment

Measures that may slow down the process of interstitial nephritis and inherent progression of renal disease are known as renoprotective therapies. These include nutritional support, and addressing electrolyte imbalances, chronic dehydration, azotemia and hyperphosphataemia.

The effect of a renal diet (reduced protein, low-phosphate diet) on cats with stable, naturally occurring stage II/III CKD have been reported as beneficial[17], with survival rates nearly double that of standard diet-fed cats (633 days on low-protein diet versus 264 days with normal diet-fed cats)[18][19].

CRD and hyperphosphatemia requires addressing in Stage II – IV renal disease, where a renal diet is indicated, as well as supplementation with an oral probiotic such as Azodyl, and phosphate binders such as Epakitin[20].

Hypertension is a common feature of CRD, although normotensive cats still have capillary hyperperfusion within the glomerulus, therefore drugs such as amlodipine besylate are the antihypertensive drug of choice in cats. Amlodipine initially is prescribed at a dose of 0.625 mg/cat and may be increased to 1.25 mg/cat in larger patients or if the desired effect is not obtained at the lower dosage. If the blood pressure cannot be controlled with amlodipine, the addition of benazepril should be considered.

Fluid therapy is vital in most cases. In mild disease, subcutaneous injection of fluids may be given weekly or fortnightly and is relatively quick and inexpensive to perform. Non-regenerative anaemia, supported by blood tests, needs to address iron supplementation, EPO and blood transfusion. There is some evidence that calcitriol administration slows renal disease progression in dogs and this approach is recommended in cats[21].

Uraemic gastritis in many cats shows as partial anorexia, or nausea rather than outright vomiting. H2 receptor antagonists are under-utilised; they function by preventing gastric HCl acid production. Famotidine 0.5mg/kg PO q 24-48 hrs or ranitidine 2-3 mg/kg q12 hrs PO may be considered whether cats seem nauseous or not.

Omega-3 fatty acid, a potent antioxidant, have been shown to increased survival rates in feline CRD[22][23].

Pentosan polysulphate has recently been shown to restore renal hemodynamics in compromised perfusion studies[24].

Since older cats with chronic renal disease commonly develop urinary tract infections caused by E. coli infection[25], cefovecin may have usefulness as an adjunct therapy.

Mesenchymal stem cell injections have recently been trialled as a therapy[26]. Six cats received a single unilateral intrarenal injeciton of autologous bone marrow-derived or adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells via ultrasound guidance. Only two cats with chronic renal disease showed modest improvements in glomerular filtration rate and a mild decrease in serum creatinine concentrations.

The prognosis of chronic renal disease is reasonable in the short-term, especially in Stage I-III, but no current treatments can slow down the invariably terminal progression of this disease. Euthanasia is advisable in cases where quality of life is poor and anorexia is persistent.

References

- ↑ Lulich, JP et al (1992) Feline renal failure: questions, answers, questions. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 12:127

- ↑ Elliott, J Watson, AD (2009) Chronic kidney disease: staging and management. In Bonagura, JD & Twedt, DC (Eds): Current veterinary therapy. XIV. Elsevier Saunders, St Louis. p:883

- ↑ August, JR (2006) Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine, Vol 5. Elsevier Saunders

- ↑ Weil AB (2010) Anesthesia for patients with renal/hepatic disease. Top Companion Anim Med 25(2):87-91

- ↑ Keegan RF & Webb CB (2010) Oxidative stress and neutrophil function in cats with chronic renal failure. J Vet Intern Med 24(3):514-519

- ↑ Yabuki A et al (2010) Comparative study of chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats: induction of myofibroblasts. Res Vet Sci 88(2):294-299

- ↑ Cavana P et al (2008) Noncongophilic fibrillary glomerulonephritis in a cat. Vet Pathol 45(3):347-351

- ↑ Brown, SA & Brown, CA (1995) Single-nephron adaptations to partial renal ablation in cats. Am J Physiol 269:R1002

- ↑ Lappin MR et al (2006) Interstitial nephritis in cats inoculated with Crandell Rees feline kidney cell lysates. J Feline Med Surg 8(5):353-356

- ↑ DiBartola SP et al (1993) Development of chronic renal disease in cats fed a commercial diet. J Am Vet Med Assoc 202(5):744-751

- ↑ Elliott, J & Barber, PJ (1998) Feline chronic renal failure: clinical findings in 80 cases diagnosed between 1992 and 1995. J Small Anim Pract 39:78

- ↑ Novellas R et al (2010) Assessment of renal vascular resistance and blood pressure in dogs and cats with renal disease. Vet Rec 166(20):618-623

- ↑ Syme, HM et al (2006) Survival of cats with naturally occurring chronic renal failure is related to severity of proteinuria. J Vet Int Med 20:528

- ↑ Jepson RE et al (2010) Measurement of urinary cauxin in geriatric cats with variable plasma creatinine concentrations and proteinuria and evaluation of urine cauxin-to-creatinine concentration ratio as a predictor of developing azotemia. Am J Vet Res 71(8):982-987

- ↑ Kinns J et al (2010) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the feline kidney. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 51(2):168-172

- ↑ Brown, SA (2010) Linking treatment to staging in chronic kidney disease. In August, JR (Ed): Consultations in feline internal medicine, Vol 6. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia. pp:475

- ↑ Elliott, J et al (2000) Survival of cats with naturally occurring renal failure: effect of conventional dietary management. J Small Anim Pract 41:235

- ↑ Roudebush P et al (2009) Therapies for feline chronic kidney disease. What is the evidence? J Feline Med Surg 11(3):195-210

- ↑ Elliott, DA (2010) Nutritional management of chronic kidney disease. In August, JR (Ed): Consultations in feline internal medicine. Vol 6. pp:137

- ↑ Ross, SJ et al (2006) Clinical evaluation of dietary modification for treatment of spontaneous chronic kidney disease in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 229:949

- ↑ Polzin, DJ et al (2009) Calcitriol. In Bonagura, JD & Twedt, DC (Eds): Current veterinary therapy XIV. Elsevier Saunders, St Louis, p:892

- ↑ Brown SA (2006) Oxidative stress and chronic kidney disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 38(1):157-166

- ↑ Brown SA et al (1996) Does modifying dietary lipids influence the progression of renal failure? Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 26(6):1277-1285

- ↑ Guan Z, Fuller BS, Yamamoto T, Cook AK, Pollock JS, Inscho EW. (2010) Pentosan Polysulfate Treatment Preserves Renal Autoregulation in Ang II-Infused Hypertensive Rats via Normalization of P2X1 Receptor Activation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol.

- ↑ Freitag T et al (2006) Antibiotic sensitivity profiles do not reliably distinguish relapsing or persisting infections from reinfections in cats with chronic renal failure and multiple diagnoses of Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. J Vet Intern Med 20(2):245-249

- ↑ Quimby, JM et al (2011) Evaluation of intrarenal mesenchymal stem cell injection for treatment of chronic kidney disease in cats: a pilot study. JFMS 13:418-426