Cytauxzoonosis is a serious, often fatal, tick-borne disease caused by the apicomplexan protozoal parasite Cytauxzoon felis. This disease affects domestic cats in the south central and south-eastern portions of the United States[1]. It is a genus of protozoa closely related to Theileria spp.

The causative organism, Cytauxzoon felis, is classified in the Order Piroplasmida, Family Theileridae. Because of the rapid onset of severe clinical illness and high mortality (historically greater than 95%) associated with this disease in domestic cats, they likely serve as accidental dead-end hosts. The natural reservoir host of C. felis is the North American bobcat (Lynx rufus). In most instances, bobcats remain asymptomatic when infected by C. felis; however, fatal infection also has been observed in this species. Ticks are believed to be the natural vector for this organism. Experimentally, an Ixodid tick (Dermatocentor variablis) has been shown to transmit C. felis from bobcats to domestic cats, causing the clinical signs associated with cytauxzoonosis. As expected, Cytauxzoonosis is seen more often during the summer months in the United States (May through September) when ticks are more likely to be found. Cats with access to the outdoors (especially wooded areas) are at higher risk of coming into contact with infected ticks and acquiring this disease[2].

Life cycle

Organisms in the genus Cytauxzoon have two stages in their life cycles: an erythrocytic piroplasm and a leukocytic or tissue phase. The leukocytic phase begins when C.felis organisms infect mononuclear phagocytes. The organisms infecting these cells undergo asexual reproduction forming schizonts. As these leukocytes become engorged with schizonts, they line the lumens of veins in many of the organs of the body, causing obstruction of blood flow. Obstruction of blood flow and ischemia are responsible for many of the clinical signs associated with this disease[3]. Subsequently, the schizonts develop into merozoites which eventually cause host cell rupture and enter the blood. These intravascular merozoites infect variable numbers of erythrocytes. The parasitemia seen on the stained blood smear often represents a late stage of disease. Infected cats typically die within a few days after the onset of parasitemia[4].

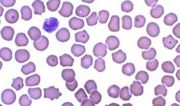

Blood smear, cat, cytauxzoonosis, Wright-Leishman stain. Signet ring forms of the parasite are present within several erythrocytes.

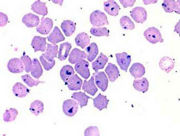

Blood smear, cat, cytauxzoonosis, Wright-Leishman stain. Abundant stain precipitate obscures hemoparasites within erythrocytes.

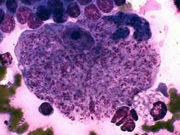

Fine-needle aspirate, spleen, cat, cytauxzoonosis, Wright-Leishman stain. Large macrophage with innumerable Cytauxzoon felis merozoites.

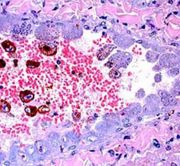

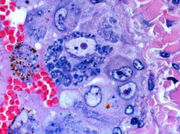

Liver, cat, cytauxzoonosis, Hematoxylin & eosin stain. View of hepatic parenchyma demonstrating macrophages with schizonts of Cytauxzoon felis.

Liver, cat, cytauxzoonosis, Hematoxylin & eosin stain. Closer view of hepatic blood vessel showing partial blockage of lumen by parasite-laden macrophages.

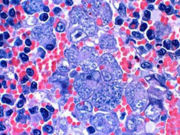

Spleen, cat, cytauxzoonosis, Hematoxylin & eosin stain. Schizogony is present within macrophages in the splenic parenchyma.

Clinical signs

The clinical signs observed in cats with Cytauxzoonosis are non-specific and usually include acute lethargy, depression, and anorexia. Infected cats also often exhibit icterus, mucous membrane pallor, and dehydration. As the disease progresses, mild to severe dyspnoea becomes apparent with concomitant radiographic evidence of moderate to severe bronchointerstitial pulmonary disease.

Less frequently, renomegaly, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly have been identified on physical examination. A fever may be present that ranges in severity from 103-107ºF. Febrile episodes usually coincide with the onset of parasitemia as observed on stained blood smears. Hypothermia, recumbency, and coma generally are signs of terminal disease[5].

Differential diagnosis includes: other causes of icterus, haemobartonellosis, Heinz body hemolytic anemia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, pyruvate kinase deficiency

Enzyme assays or specialized DNA tests used to identify pyruvate kinase or phosphofructokinase deficiencies

Diagnosis

Respiratory distress in common in affected cats. It seems likely that macrophage activation and inflammatory mediators lead to an interstitial pneumonic process characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates and pulmonary edema[6].

A leukopenia with a left shift and toxic changes of neutrophils, thrombocytopenia, and a normocytic, normochromic, non-regenerative anaemia may be seen. Abnormal hemostasis may be present from disseminated intravascular coagulation. Common abnormalities in the biochemical profile may include hyperbilirubinemia, hyperglycemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypokalemia, and increased activity of alanine aminotransferase. In many cases, marked bilirubinuria is observed[7].

Diagnosis of Cytauxzoonosis is made by identifying piroplasms within erythrocytes in the stained blood smear. These erythroparasites may appear as round to oval “signet rings” (1-1.5 µm in diameter); bipolar, oval, “safety pin” forms (1-2 µm in diameter); tetrad forms; or anaplasmoid round “dots” (less than 0.5 µm in diameter). The anaplasmoid form may appear as single organisms or as multiple organisms resembling chains. Microscopically, the piroplasms have a small, peripherally-located nucleus that stains dark red to purple with a off white to light blue cytoplasm when using Giemsa stain. The number of erythrocytes parasitized with C. felis varies among cats and with the stage of disease. However, the percentage of affected erythrocytes usually is low. Infrequently, large mononuclear phagocytes containing developing merozoites can be seen at the feathered edge of peripheral smears. These parasite-laden macrophages may measure 75 µm in diameter[8].

When detection of parasitized erythrocytes is difficult in the stained blood smear, fine-needle aspirates of the spleen, lymph nodes, or bone marrow may provide a diagnosis. In these cases, the large, merozoite-laden macrophages may be readily observed. Other methods used to diagnose cytauxzoonosis in cats include a direct fluorescent antibody test for detection of the tissue phase of the parasite and a microfluorometric immunoassay system to detect serum antibody to the organism. However, these tests are largely experimental and generally are not available commercially.

Because of the extremely rapid course of illness associated with cytauxzoonosis, a diagnosis is often made by post-mortem examination. Grossly, dehydration, generalized pallor, and/or icterus may be observed. Other common findings at necropsy include enlarged, oedematous, and reddened lymph nodes; distended abdominal veins (especially splenic, mesenteric, and renal veins); petechial and ecchymotic haemorrhages of abdominal organs, heart, and lungs; large dark spleen; and congested, oedematous lungs.

Impression smears of affected tissues are usually diagnostic. Large mononuclear phagocytes (engorged with schizonts and developing merozoites) are readily identified within tissue imprints. On histopathology, schizont-containing macrophages are prominent within the lumens of larger blood vessels, especially in tissue sections of lung, spleen, and liver (Fig 5). These parasite-laden macrophages may be identified free within the lumen or attached to wall of the vessel, often appearing to occlude the vessel. Despite the severity of infection, very few signs of inflammation are evident histologically.

Treatment

Although the prognosis is poor, some cats respond to treatment with diminazene aceturate or imidocarb dipropionate (along with aggressive supportive care).

Some cases may recover without antiprotozoal therapy (although some cats remained parasitemic and could be a potential source of infection for naive cats)[9].

Alternative combinations, such as atovaquone at 15 mg/kg p.o. q 8h and azithromycin at 10 mg/kg p.o. q 24 h appears promising in clinical trials with cats[10][11].

No vaccine is currently available as a preventative measure in cats.

References

- ↑ Holman PJ & Snowden KF (2009) Canine hepatozoonosis and babesiosis, and feline cytauxzoonosis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 39(6):1035-1053

- ↑ Blouin, EF et al (1987) Evidence of a limited schizogonous cycle for Cytauxzoon felis in bobcats following exposure to infected ticks. J Wildlife Dis 23:499

- ↑ Meinkoth J, Kocan AA, Whitworth L, et al (2000) Cats surviving natural infection with Cytauxzoon felis: 18 cases (1997-1998). Vet Intern Med 14:521-525

- ↑ Cowell RL, Panciera RJ, Fox JC, et al (1988) Feline cytauxzoonosis. Comp Cont Edu 10:731-736

- ↑ Meier HT, Moore LE. (2000) Feline cytauxzoonosis: A case report and literature review. J Am Vet Med Assoc 36:493-496

- ↑ Snider TA, Confer AW, Payton ME. (2010) Pulmonary Histopathology of Cytauxzoon felis Infections in the Cat. Vet Pathol 47(2)

- ↑ Franks PT, Harvey JW, Shields RP, et al (1987) Hematological findings in experimental feline cytauxzoonosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 24:395-401

- ↑ Hoover JP, Walker DB, Hedges JD. (1994) Cytauxzoonosis in cats: Eight cases (1985-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 205:455-460

- ↑ Greene CE, Latimer K, Hopper E, et al (1999) Administration of diminazene aceturate or imidocarb dipropionate for treatment of cytauxzoonosis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 214:497-500

- ↑ Birkenheuer, AJ et al (2008) Atovaquone and azithromycin for the treatment of Cytauxzoon felis J Vet Intern Med 22:703

- ↑ Cohn LA et al (2011) Efficacy of atovaquone and azithromycin or imidocarb dipropionate in cats with acute cytauxzoonosis. J Vet Intern Med 25(1):55-60